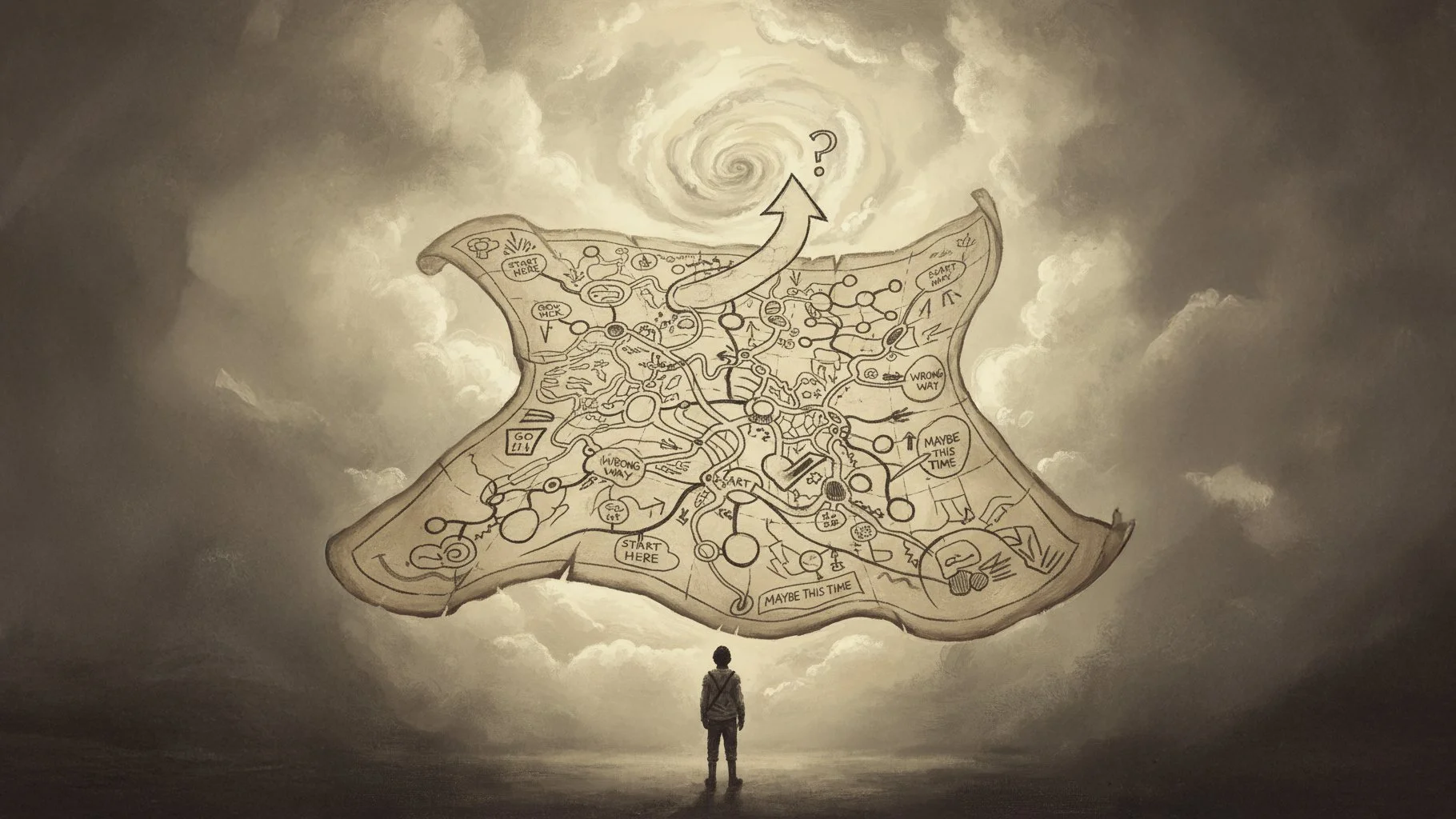

Why I Ditched Long-Term Goals

Mathew Dalby on trading decade-long plans for 12-month focus. Why short-term goals build momentum, creativity, and joy — and how StudioFAB thrives on quick, sharp projects.

The Big Plan Illusion

For years, I adored a grand plan. The ten-year strategy. The whiteboard full of arrows. The “by the time I’m fifty, I’ll have…” list.

But here’s the quiet truth I’ve learned: long-term goals are often fool’s gold.

They sound noble, but they dangle just far enough away to keep you forever reaching, never arriving. You chase something so distant that you stop noticing the side quests — the unexpected turns, obsessions, people, or ideas that might’ve become something extraordinary if you weren’t so blinkered by your plan.

The Power of the Side Quest

History’s full of proof that detours can be more fruitful than destinations.

Columbus set out for India and found the Americas.

Fleming was trying to grow bacteria and stumbled upon penicillin.

Percy Spencer was testing radar equipment when a chocolate bar melted in his pocket — and voilà, the microwave was born.

None of them were following a decade-long roadmap. They were curious, awake, and paying attention to the world as it actually was, not how they’d planned it to be.

StudioFAB and the Short Game

At StudioFAB, we see the same thing in design.

Everyone loves the big projects — the ones that take years, a small army of consultants, and entire walls of drawings. And they’re brilliant, of course. But the short, sharp ones — the pop-up competition entries, the rebranding sprints, the one-off hospitality refreshes — those are where we stretch a different set of muscles.

They demand focus, speed, and instinct. You make decisions fast. You trust your gut. You find clever shortcuts. You rediscover agility. And sometimes, you surprise yourself with how inventive you can be when you don’t have the luxury of time.

Necessity is still the mother of invention.

Give me half a dozen quick, compact projects over one big behemoth any day. They keep the studio nimble, creative, and alert — and they remind us that brilliance doesn’t always need a three-year timeline or a $30 million budget. Sometimes it just needs a spark, a deadline, and a good cup of coffee.

Why Short-Term Wins Matter

These days, I set twelve-to-eighteen-month goals.

Tight, focused bursts. Something I can define, touch, complete. Then move on.

The win is real. The progress visible. The energy stays alive.

You learn faster, adapt quicker, and avoid the emotional fatigue of chasing a horizon that never gets closer. Small goals keep your momentum human — fast enough to feel progress, slow enough to notice the scenery.

Myopia and Missed Sunsets

When you live in long-term goal mode, you risk a kind of blindness. You’re so fixated on the destination that you miss the texture of the journey — the people you meet, the moments of calm, the small wins that quietly build a good life.

Let’s not trade every sunrise and sunset for a dream that might never deliver what you think it will.

Because those are the real dividends — the ones you don’t see until you stop staring at the far-off peak and notice the light on the horizon.

Small Stones, Big Path

Enough short-term goals, stacked with intent, tend to form a long-term one anyway.

But you’ll have lived far more of your life getting there.

No decade-long manifestos. No “vision boards for 2035.”

Just the next clear, achievable thing — done properly, with presence, and a little joy along the way.

You can keep chasing the summit if you like.

I’m happier building the path — one small, beautiful stone at a time.

This Weekend, I Became an International Award-Winning Screenwriter.

This weekend, I became an international award-winning screenwriter. What began as a late-night creative experiment has become an unexpected extension of StudioFAB — a reminder that design and storytelling are two sides of the same creative coin.

This weekend, I became an award-winning screenwriter.

Which is both delightful and faintly ridiculous. Delightful because it is true, and ridiculous because I still half expect someone to tap me on the shoulder and say, “All very amusing, Mathew, but back to the hotel drawings, please.”

I took up screenwriting late last year as a serious hobby.

Not golf. Not pottery. Screenwriting.

I thought it would be a harmless creative detour. A bit of cerebral stretching. Something to do when the rest of the house was asleep and the world had stopped demanding floor plans and value engineering.

The Accidental Writer

Fast forward a few months, and somehow there are now three screenplays with my name on them. Each has either won or placed in international competitions, and one of my other scripts is currently with a production company in Los Angeles.

It’s all a bit surreal.

But here’s the truth: writing didn’t feel like learning something new. It felt like remembering something familiar. After thirty years of designing hotels, homes, and the occasional palace, I realised that what I really do for a living is tell stories. Screenwriting is simply design without walls. The materials are different, but the purpose is the same.

Both ask: what do I want someone to feel?

Design, Story, and the Same Question

Design has always been my language. I choreograph light, texture, and space to build emotion. A lobby is an opening act. A corridor is suspense. A guestroom is resolution. The story of arrival, pause, and rest.

Writing is the same, except your tools are dialogue, tension, and silence. You still craft rhythm. You still edit ruthlessly. You still pray no one notices the joins.

Both fields demand empathy. A hotel succeeds when it anticipates its guests’ emotions before they do. A film succeeds when the audience recognises themselves in the characters. You build both from the inside out. You design for feeling, not function.

Lessons Between Two Worlds

Design taught me patience. Projects can take years. You learn to trust the slow burn. Screenwriting, on the other hand, demands precision. You have ninety pages to make someone care.

It’s merciless.

Every word must pay rent.

Yet that discipline makes me sharper back in the studio. I now look at drawings like dialogue. If a line doesn’t advance the story, it goes.

Creativity isn’t about invention. It’s about listening. When you design a space or write a character, you listen for what it wants to be. You remove what’s false until what’s left feels inevitable. That’s when it’s right.

On Winning (and Not Losing Focus)

The funny thing about winning awards is that people assume you had a plan. I didn’t. I entered one festival because the submission link popped up at midnight, and I thought, Why not.

Then I heard I’d made it to the finals, well, I was going to go anyway. But when they announced my name…

But once the disbelief wore off, what stayed with me wasn’t pride.

It was perspective.

Creativity doesn’t care about categories. It finds new rooms to inhabit.

And before anyone wonders, NO, I’m not taking my eye off StudioFAB.

Quite the opposite.

Writing has sharpened it. It’s made me see design in new ways, tighter, bolder, more narrative-driven.

StudioFAB remains my focus, my craft, and my home. The screenplays are simply another expression of the same creative muscle. I see it as a parallel practice that feeds back into how we think, how we see, and how we design.

Night Work

I still spend my days leading the studio, working with architects, builders, and hoteliers to craft spaces that make sense of chaos. But at night, I slip into another kind of world-building. One where walls are made of words, where atmosphere lives in subtext, and the soundtrack is the gentle snoring of the dogs.

It’s slower, lonelier, and oddly liberating.

Storytelling, in any form, is the purest act of empathy. You create a structure for someone else to step into, a place to feel something safely. Whether that space is a courtyard or a scene in a film hardly matters. Both are invitations.

Rediscovering Play

Screenwriting reminded me of something I’d quietly lost in design, the idea of play, the unguarded joy of making something purely because you can.

In design, we often prioritise pragmatism and accountability over curiosity, making it a luxury.

Writing reintroduced it.

That spark of let’s see what happens if…

Both my worlds feed each other. Writing makes me observant. Design keeps me grounded. One deals in story, the other in structure. Together, they form the full circle of creativity.

Staying Grounded

When a script began to gain traction in Los Angeles, a friend asked if I was tempted to leave design behind.

Not a chance.

The joy lies in the crossover.

To move from drawing a lobby to writing a scene is to shift between two dialects of the same language.

StudioFAB remains the engine. The writing simply adds a new instrument to the orchestra. The focus, as always, is on building, whether it’s a space or a story.

Closing Thoughts

So yes. This weekend, I became an award-winning screenwriter. And on Monday morning, I went straight back to the studio. The two are not at odds. They are the same craft, played in different keys.

Creativity doesn’t live in compartments.

It leaks.

It overlaps.

It misbehaves.

And that is precisely what keeps it alive.

The Gift of Constraint (and Why Perfection Needs a Good Kick in the Shins)

We tend to treat constraints as enemies — the budget too small, the site too narrow, the client too picky. But limits don’t kill creativity, they ignite it. The best work happens when you stop trying to do everything and start focusing on what matters. Here’s how structure, restraint, and a touch of discomfort can turn frustration into innovation.

“The very things that held you down are gonna carry you up and up and up!”

In the summer of 1501, Florence was facing a very Italian problem. Lying flat in the cathedral courtyard was a massive slab of marble, abandoned by two sculptors and described rather tragically as “a certain man of marble, badly blocked out and laid on its back.”

You can picture it, can’t you? A once-promising block, left sunburnt and pigeon-kissed, a sort of marble roadkill in the Renaissance sunshine.

For forty years, it sat there, too flawed to use and too precious to throw away. Then along came a 26-year-old sculptor, barely out of artistic adolescence, and with the sort of misplaced confidence we usually associate with first-year architecture students.

He took one look and said, “I’ll take it.”

The marble was awkwardly narrow, riddled with veins, and so brittle it made everyone nervous. But instead of fighting against the constraint, the sculptor leaned into it. The slab dictated the pose, the tilt of the head, even the famously oversized right hand — all the product of necessity rather than whim. The sword and Goliath’s head? Not missing, merely uninvited. There simply wasn’t room.

The sculptor was Michelangelo, and the sculpture was probably the most famous piece in the world, David.

It was the world’s greatest case of make-do and mend.

When finished, the statue was so magnificent (and so heavy) that the cathedral roof creaked at the thought of it. A committee — including Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci — sensibly decided it would look far better on the ground, preferably where people could actually see it. And there it stood, redefining sculpture and proving once and for all that constraints don’t strangle creativity, they sculpt it.

Oh, yeah, his right hand is too big!

Constraint: the secret ingredient

As designers, we tend to groan when faced with limitations. Budgets, deadlines, local council guidelines written by people who have clearly never designed anything in their lives — all of it can feel maddening. But here’s the thing: creativity without constraint is chaos.

A blank page offers infinite freedom, which is another way of saying endless panic. Give that same designer a boundary, and they’ll turn into MacGyver with a mood board.

The value of design lies as much in what you leave out as what you put in. A great space breathes because you resisted the urge to fill every corner. A great idea sings because you stopped one verse earlier than expected.

Think of the Japanese haiku: seventeen syllables to express an entire season, a lifetime, or the unbearable tenderness of a falling leaf. Limitation, as it turns out, is poetry’s favourite muse.

Dr Seuss knew it, too. Challenged to write a children’s book using no more than fifty words, he produced Green Eggs and Ham, which went on to sell two hundred million copies. Proof, if ever you needed it, that being boxed in sometimes helps you think outside it.

The illusion of certainty

Our modern brains despise uncertainty. They rush to fill the silence with assumptions — quick, comforting, and often wrong. Psychologists call it confirmation bias. I call it creative taxidermy: everything looks alive, but nothing’s actually moving.

So, how do we keep the work alive when the unknown is breathing down our necks?

First, use three kinds of thinking in sequence, not all at once

Divergent thinking. Open the windows. Generate options, variations, and delicious oddities. Quantity before quality.

Convergent thinking. Close the windows. Sort, cluster, compare, and choose. Commit to a path.

Metacognition. Step onto the balcony. Notice how you are thinking, not just what you are thinking. Plan, monitor, and adjust your own process.

Now, give that trio a practical runway.

Do not sprint to a solution. Define the shape of the problem. Clarify the outcome you actually need. Write the challenge in one clean sentence. Then write the best-case scenario in one more. If it takes three, you do not yet understand it.

Remove assumptions. Make a list of everything you think is true. Cross out every line that you cannot back with evidence. Keep only facts.

Work the classic questions. What, Why, Who, When, Where, and How. Simple questions, ruthless discipline.

Ask Why, then Why again, and again, until the root presents itself. The Five Whys originated as a Toyota habit and remains an elegant way to dig beyond symptoms and uncover their causes.

Balance collaboration with solitude. Invite the room to diverge, then give people private thinking time before you converge. It reduces the risk of homogeneity, that slow drift toward agreeable mush. In the literature, it is referred to as groupthink, where the desire for harmony stifles alternatives. Do not let a tidy meeting strangle a good idea.

Test head and heart. Give each option a simple score out of ten for logic and a simple score out of ten for feeling. If the numbers wobble, you probably need to refine the brief or push the idea further out to the edge and bring it back with something worth keeping.

Once the shape is finally visible, create a plan. One page. Milestones, owners, and a date when you will judge success with cold eyes.

Extra Courage required?

And if you want a little courage for the road, remember a few true tales of persistence under constraint. Dr Seuss wrote Green Eggs and Ham using only fifty distinct words after a fifty-dollar bet from his publisher, and it became his most successful book—constraint in action.

J K Rowling’s first Harry Potter manuscript was turned down again and again before Bloomsbury said yes, a reminder that rejection often signals timing, not talent.

Angry Birds was not a first swing; it was Rovio’s fifty-second game, the one that kept the lights on.

As for Walt Disney, people often quote a specific tally of rejections, which is difficult to verify. What is clear is that many investors passed before television, money, and banking partners backed the park, and that is the part that matters for us.

The stuff of dreams OR that nightmares are made of…

“The right yes is often later than you expect. ”

Creativity does not live in knowing. It lives in not knowing. It is the delicate wobble just before a form reveals itself. It is stepping out on thin ice and listening to the cracks grow louder, until you finally break through and feel the cold bite of something real. That is the point. That is where ideas breathe.

So, the next time you are staring down a tight budget, a contrary site, or a brief that reads like a riddle inside a spreadsheet, do what Michelangelo did with his ill-tempered marble. Use it. Shape with it. Let it answer back. Your constraint is not an obstacle. It is the chisel in your hand.

Perfection is overrated. A little pressure never hurt a masterpiece.